|

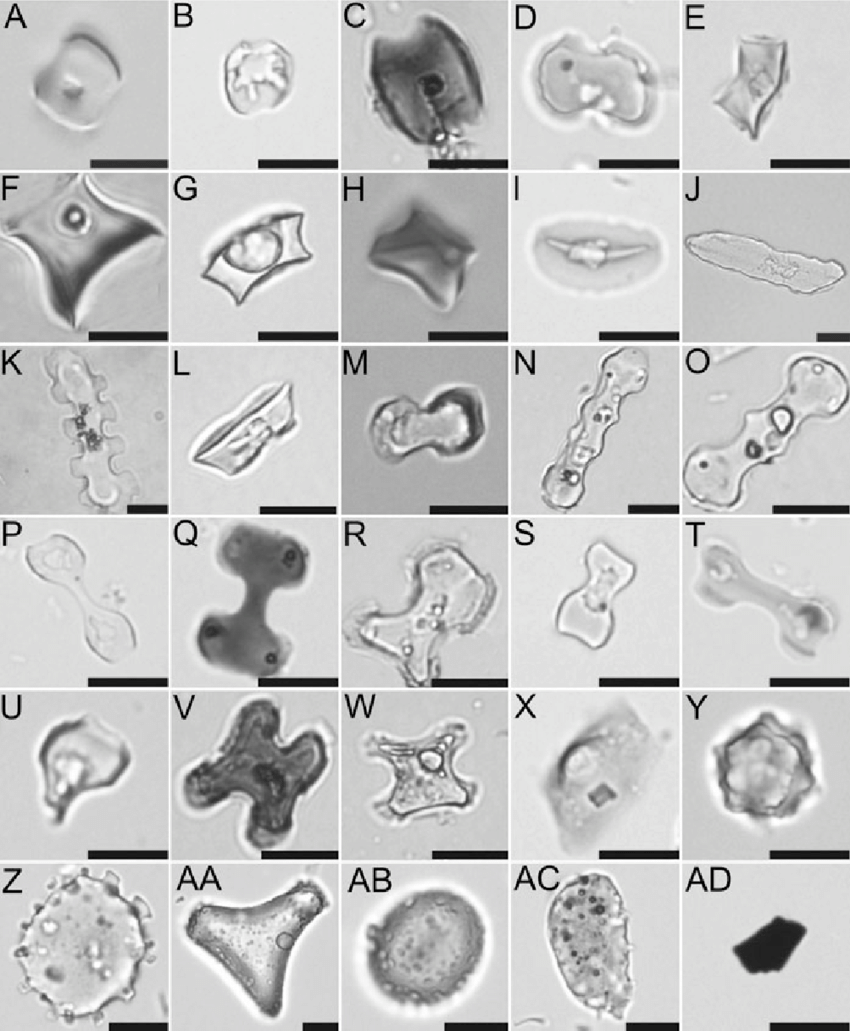

The word “phytolith” comes from the Greek words for “plant” and “stone,” and that does a good job summarizing what a phytolith is: they are basically tiny rocks inside of plant cells. When plants grow, they absorb water and nutrients through their roots. During this process, they also absorb dissolved minerals like silica, which is essentially the same material as rocks. These minerals get deposited inside plant cells, and get left behind in the soil after the plant dies because they are inorganic–they don’t decompose like the rest of the carbon-based plant tissue. The silica molecules form a perfect “cast” of the cell, or the little spaces in between the cells. To me, phytoliths look a little bit like snowflakes under the microscope. Like pollen, different plants produce phytoliths with different shapes and sizes, so we can match the phytoliths we extract from archaeological excavations with certain plants that grew at that site. Also like pollen, archaeological sediment needs to undergo a series of chemical rinses and processes in order to separate the phytoliths from the surrounding dirt. The final product is a dusting of phytoliths on a slide, which goes under the microscope. Phytolith analysis is often used to learn about ancient diets, environments, agriculture, and plant domestication. Often, archaeologists will use phytoliths alongside other methods, like pollen or DNA analysis. At an archaeological site in northeast China, a team of researchers used phytoliths to reconstruct ancient environments and better understand agricultural practices. Based on the discovery of millet and other phytoliths, the archaeologists found that the environment in the area of the site was warm and wet about 6,500 to 5,600 years ago, which was ideal for agriculture, and led to a prosperous time in the area.

I used phytolith analysis in my Ph.D. dissertation on sediments from Massachusetts. I studied phytolith data from two 17th century English homestead sites, where I found evidence of corn agriculture. This was interesting and a little bit surprising, because English colonists did not like eating corn in the early 1600s–they much preferred wheat, which was more common in Europe. In my research, I used corn to talk about how English colonists adapted to life in the Americas through the consumption of Indigenous foods. This blog post was partially adapted from a YouTube video I wrote with Smiti Nathan for her channel @smitinathan.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorAnya Gruber Archives

December 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed