|

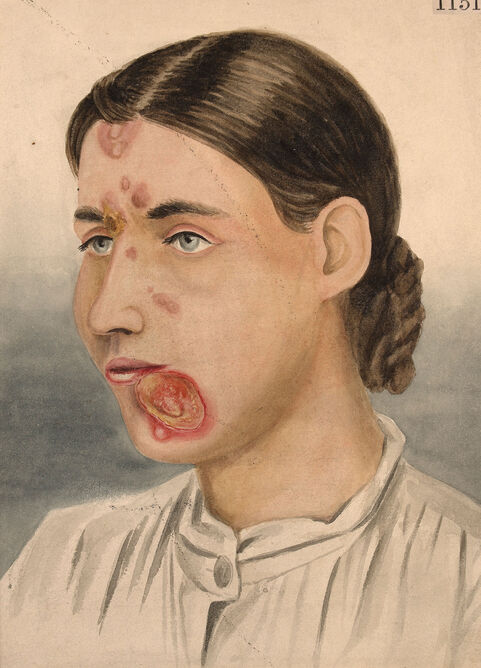

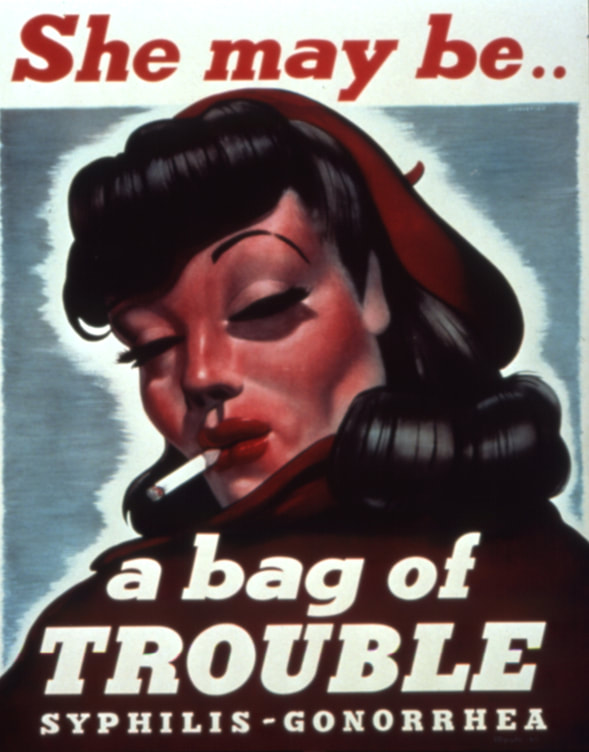

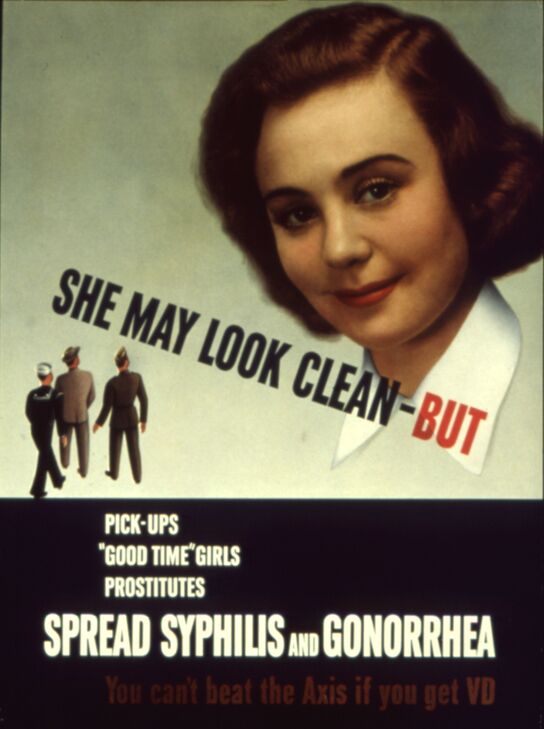

Al Capone, Friedrich Nietzsche, Leo Tolstoy, James Joyce, and Vladimir Lenin–what do these people have in common? They all suffered from syphilis. As one of the most feared diseases in existence, syphilis has caused immense suffering for thousands of years. Shakespeare even called syphilis “the infinite malady,” referencing the deep and terrible history of the disease. While archaeologists study many different infectious diseases that have caused epidemics over the years, syphilis is particularly interesting. Why? Because it leaves behind striking archaeological clues about the disease and it’s impact on society. Syphilis is caused by a corkscrew-shaped bacterium called Treponema pallidum. Syphilis is primarily a sexually transmitted disease, but it can also be congenital, meaning it can be passed to a fetus during pregnancy, leading to a child being born with a syphilis infection. Historically nicknamed “The Great Pretender,” syphilis mimics the symptoms of many other infectious diseases, which can make it hard to diagnose or confuse with other illnesses. There are three main stages of syphilis infection–primary, secondary, and tertiary. Each stage has a characteristic set of symptoms. The most notable symptoms of primary and secondary stage syphilis are sores in the mouth or genital area and a rash across the body, especially on the face, hands, and feet. Tertiary stage syphilis is notoriously painful and debilitating, causing severe damage to the skin, brain, heart, and spinal column, which can lead to paralysis, tumor-like growths, dementia, organ failure, and in many cases, death. Secondary and tertiary syphilis can infect the bone–especially the tibia, sternum, clavicles, and skull. The infection creates holes, making the bone look moth-eaten. This usually leads to severe pain, as well as neurological symptoms like confusion, memory loss, and personality changes. The lesions and marks on the bones are still visible, even after hundreds or thousands of years, making it one of the best archaeological clues we have for syphilis. The characteristic patterns syphilis can leave on bones provide us with information we would likely otherwise not know. First off, bones are one of the best clues to help us figure out where syphilis came from. There is a lot of scientific debate surrounding the early origins of syphilis. The leading hypothesis is that syphilis originated in the Americas, and then spread to Europe, Asia, Australia, and Africa via colonization in the 1400s and 1500s. Some scholars argue that it was already present in Europe prior to colonization, but others believe that historical descriptions of syphilis-like cases from before the 1490s were actually leprosy. Archaeologists have investigated this mystery by studying skeletal remains. Some of the earliest evidence of syphilis was recovered from a cave in Brazil. A team of researchers found the remains of a child who died about 9,400 years ago. Based on the marks on this child’s bones, they likely suffered from congenital syphilis. This study is important because it shows that syphilis has existed in the Americas for at least 10,000 years. In addition to bones, historical records can also provide clues about the origins of syphilis. The first recorded epidemic of syphilis in Europe occurred among soldiers in the French army when Charles VIII invaded Naples in 1495. Early outbreaks were extremely infectious, particularly deadly, and often associated with warfare. A Venetian doctor wrote of this new illness: “Through sexual contact, an ailment which is new or at least unknown to previous doctors, the French sickness has worked its way in from the west to the spot as I write. The entire body is so repulsive to look at and the suffering is so great, especially at night, that this sickness is even more horrifying than incurable leprosy or elephantiasis and it can be fatal.”Clues from the historical records also show us that 15th century Europeans tended to blame the sudden emergence of this disease on their political enemies–for example, it was known as “the French sickness” in England, Italy, and Germany, while it was the “Polish disease” in Russia, and the “Christian Disease” in Turkey. The modern name “syphilis” comes from an epic poem written by an Italian scholar in the early 16th century, but didn’t become widely accepted until the early 18th century. Throughout the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, syphilis outbreaks terrorized Europe. We have clues about this from a few places. Archaeologists working at a cemetery associated with a monastic hospital in Eastern Iceland have found evidence of an outbreak of syphilis between the years of 1496 and 1554. This finding was significant because it shows how transmissible syphilis is–even somewhere as isolated as Iceland suffered from deadly epidemics. In England, between the years of 1773 and 1776, almost 30% of people admitted to London’s hospitals were victims of sexually transmitted infections, particularly syphilis. In Bologna, Italy, archaeologists studied skeletal remains from a late Medieval period Jewish cemetery and found about 400 individuals with the bone damage associated with tertiary stage syphilis. At this period in history, Jewish people were largely marginalized from mainstream European society, and researchers believe this outbreak may have worsened prejudices against this community. From Europe, syphilis spread to Asia and Africa. While sites across Asia and Africa are largely understudied in terms of the archaeology of infectious diseases, a team of researchers working near Seoul, South Korea identified a case of tertiary-stage syphilis from skeletal remains dating to the mid-1800s. This study provides important clues about the spread of this disease across the world. While syphilis was causing epidemics across Europe, Asia, and Africa, it persisted in the Americas. Archaeologists working at a 17th century cemetery in Mexico City extracted three different strains of the bacterium that causes syphilis, marking an important step in understanding the evolutionary history of this disease. In the early 1900s, syphilis posed a serious problem for military personnel during World War I. Prevention campaigns were specifically targeted to soldiers in the war. Sexually transmitted infections, including syphilis, were some of the leading reasons U.S. soldiers were medically discharged. The U.S. government funneled money into anti-prostitution laws, attempting to mitigate the spread of the sexually transmitted infection. As the U.S. secretary of war proposed in 1918: “Ten miles from any military camp, station, fort… within which it shall be unlawful to engage in prostitution or to aid or abet prostitution or to procure or solicit for purposes of prostitution, or to keep or set up a house of ill fame, brothel, or bawdy house, or to receive any person purposes of lewdness.”While the syphilis’s history is quite grim, luckily, it is now successfully treatable. Since the disease is caused by a bacterial infection, it can be effectively treated with antibiotics. However, before the invention of Penicillin in the 1940s, people treated syphilis in a variety of ways, many of which were actually pretty dangerous, and probably didn’t do much to help. A big part of syphilis’ archaeological trail is not just the disease itself, but how people tried to treat it throughout history. In fact, certain historical treatments made the illness worse, in most cases. From the 16th century through the early 19th century in England, there was one particular treatment that was widely accepted and commonplace. Typically, patients would take compounds of this treatment orally or as an injection, and treatment would last for weeks to months. Sometimes, people would rub this treatment directly onto the infected areas of their body, including their genitals. Unfortunately, this treatment turned out to be extremely toxic, and caused severe side effects including tremors, muscle spasms, headaches, kidney damage, insomnia, exhaustions, and a host of other symptoms. That treatment was mercury. Archaeologists can trace the use of mercury as a syphilis treatment by studying the most reliable syphilis archaeological clue - bones. When it comes to bones, studies conducted across Europe have shown that mercury persists in bone long after an individual has died, and this can be a useful way of understanding medical practices. But there's another clue: to find out more, let’s go to Denmark. Here, archaeologists measured the amounts of mercury in the soil from a medieval cemetery and found that 40% of syphilis cases were treated with this toxic metal. They also found that the monks who cared for sick patients experienced mercury poisoning. Similarly, at a medieval cemetery in Poland, archaeologists found that two women were likely treated with mercury, based on the high levels of it in their bones. So bones and soil work together to help up us locate mercury in the archaeological record. The archaeology of syphilis is deeply interwoven with the history of classism, misogyny, and racism. Syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases have been extremely stigmatized. Especially since the 1800s, people who suffered from syphilis have been seen as “unclean,” especially those who were marginalized by society, like women, people of color, and people of low economic status. Sexually transmitted diseases were also believed to only infect people who were “immoral,” or led sinful lives. Unfortunately, the long-term effects of this can still be felt today–scientists have shown that STI testing and treatment is still inaccessible to communities across the world, especially those who experience social and economic marginalization. Throughout history, the spread of sexually transmitted infections were commonly blamed on women and we have some clear clues indicating this. As you can see by some of these posters from the early and mid-1900s, men were encouraged to stay away from “loose women” who were perceived as the main source of syphilis, even though women are no more likely to spread syphilis or any other disease than people of other genders. In fact, the association between women and sexually transmitted infections was the origin of the now outdated term “venereal disease”: the root of “venereal” comes from the name of the goddess of love herself, Venus. It was often said that a rendezvous with Venus came with the risk of coming down with a nasty infection. This, along with the use of mercury to treat syphilis, gave rise to a 19th century saying: “a night with Venus, and a lifetime with mercury.” The historical blame of women has perpetuated stigmas and stereotypes that unfortunately still persist to this day. And you can’t really talk about syphilis without talking about one of the most egregious instances of medical abuse in history, which took place for 40 years between 1932 and 1972 in Macon, Alabama. In what is now known as the “U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee,” researchers conducted an unethical study of the effects of untreated syphilis on a group of Black men. The researchers did not receive informed consent from the people they were studying, and did not offer them treatment, even after penicillin was introduced in 1942. In 1972, when the human rights violation that was this study came to light, the researchers were rightfully criticized. They were reviewed by a panel, which wrote that the study was, quote, “ethically unjustified” and that, quote, “results [were] disproportionately meager compared with known risks to human subjects involved.” The fact that these men were Black and poor is significant. The researchers running the Tueskegee study targeted people of color because they mistakenly believed that non-white people were more susceptible to sexually transmitted diseases. In 1973, class action lawsuits were filed on behalf of the men who suffered from untreated syphilis and their families. The Tuskegee study is routinely cited as a major impetus for the development of informed consent, and its legacy can still be felt today. Since penicillin was introduced as an effective treatment for syphilis, overall cases have significantly dropped. However, over the past 20 or so years, cases have actually started to climb. According to the CDC, there were 176,713 reported cases of syphilis in the United States in 2021. That’s up from 5,979 reported in 2000, and 13,774 reported in 2010. Syphilis has had a long history that has left behind archaeological clues of its origin, spread, and severity; however, even with learning more about it’s past and present, it doesn’t seem to be going away any time soon in the future. Where Can I Go to Get Tested For STDs? | Testing Center Info Which STD Tests Should I Get? | Prevention | STDs | CDC What is Syphilis? This blog post was partially adapted from a YouTube video I wrote with Smiti Nathan for her channel @smitinathan.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorAnya Gruber Archives

December 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed